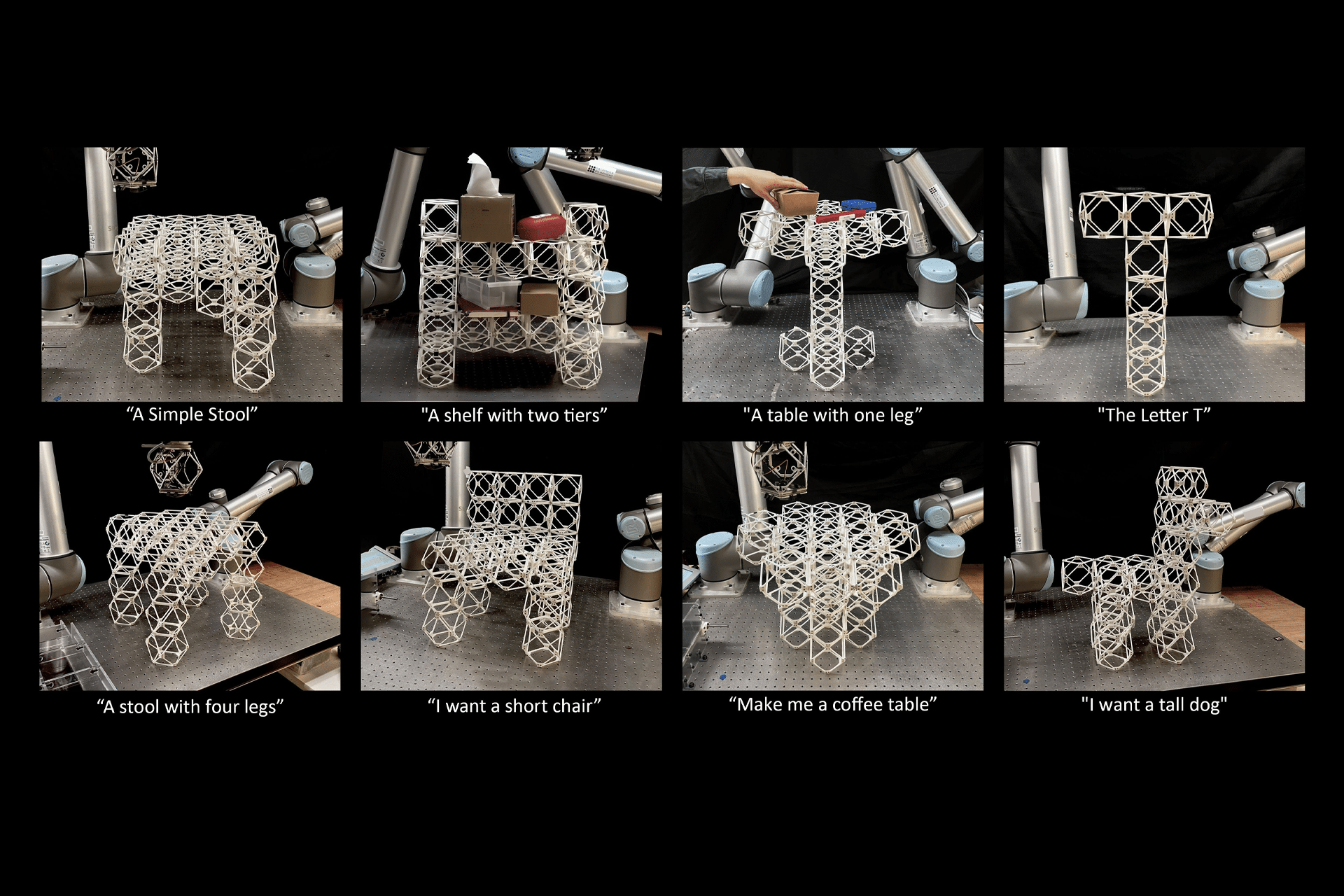

Researchers at MIT have built a speech to reality system that takes a simple spoken request for an object and turns it into something physical that can be picked up, sat on, or placed in a room. A user can ask for a basic stool, a compact table, a small shelving unit, or even a decorative figure, and a robotic arm assembles the object from modular components within a matter of minutes. The project links speech recognition, large language models, 3D generative AI, geometric processing, and robotic assembly into one continuous pipeline, aimed at letting people with no design or fabrication background create useful objects on demand.

At the start of the workflow, the system listens to a natural-language request and converts it to text. A language model interprets that instruction and produces a structured description of what the object should be, including overall shape and intended function. That description is passed to a 3D generative AI model, which outputs a digital mesh representing the object. Rather than sending this mesh directly to a 3D printer, the system converts it into a form that can be built from standard modular parts, keeping the fabrication process fast and reusable across many designs.

Designing a Voice Driven Fabrication Pipeline

To bridge the gap between a free-form mesh and a buildable structure, the team uses a voxel-based representation. The mesh is decomposed into a grid of small volumetric units that can be mapped to physical building blocks. These units form a lattice-like structure that approximates the original design while remaining compatible with a limited set of modular components. A geometric processing stage checks that these components connect cleanly, support weight where needed, and avoid excessive overhangs that would be difficult for a robot to assemble.

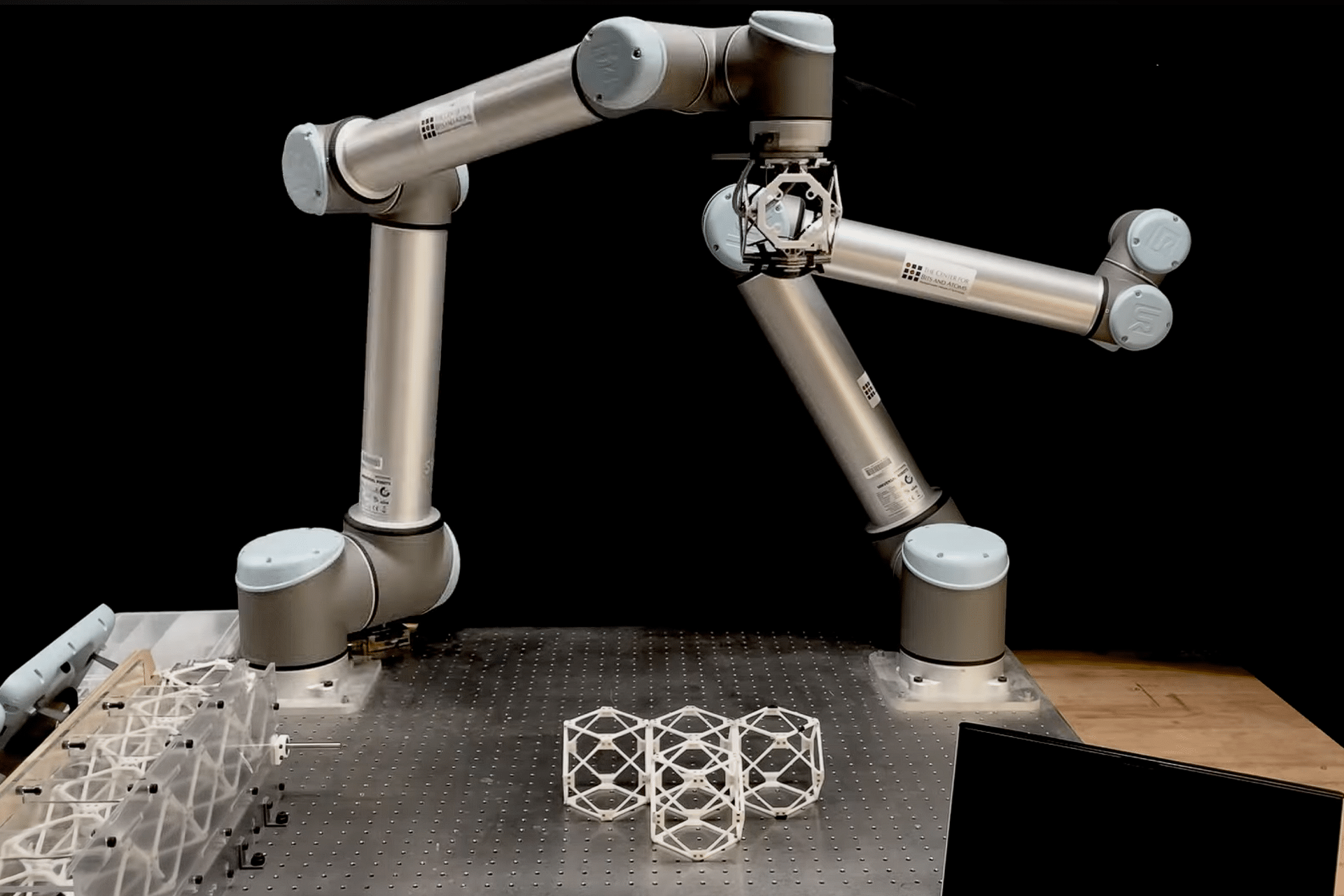

Once the voxel structure has been validated, the system computes an assembly sequence that a six-axis robotic arm can execute safely. It plans the order in which each block should be placed, the path the arm will follow to avoid collisions, and the contact points that ensure the final object is stable. The robot then picks components from a tray and snaps them into place on an assembly surface, gradually building up the requested object. In demonstrations, the system has produced stools, chairs, small tables, shelves, and decorative pieces, including a dog-shaped figure, with assembly times on the order of five minutes for simpler designs.

The speech to reality system grew out of work in MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms and the Morningside Academy for Design. Lead researcher Alexander Htet Kyaw began exploring the idea in a course focused on hands-on digital fabrication and continued it as a graduate project that spans architecture, electrical engineering, and computer science. Collaborators from mechanical engineering and CBA contributed to the robotics, hardware, and fabrication aspects, turning an early class experiment into a full pipeline that runs from spoken input through to an autonomous robotic build.

Modular Components and Robotic Assembly

Instead of manufacturing custom pieces for each new object, the system relies on a consistent library of modular blocks. These components are designed to connect in multiple configurations, which makes it possible to reuse the same parts across different furniture or decor items. A stool can be disassembled and the blocks can later be rearranged to form a short shelf, a low table, or a different seating design. This approach reduces material waste and avoids long fabrication times, while still supporting a range of shapes that the generative AI can propose.

The choice of discrete assembly also responds to limitations that arise when sending generative AI outputs straight to continuous fabrication methods. Text-to-3D models can produce many theoretical designs, but not all of them translate well into real-world objects. Issues such as thin features, unsupported spans, and complex internal cavities can lead to fragile prints or lengthy production times. By constraining the output to a lattice made from robust, repeatable modules, the speech to reality system gives the robot a more predictable task and encourages designs that can be built quickly and handled safely.

In early prototypes, the blocks are often held together with embedded magnets, which makes assembly and disassembly simple and allows for quick experiments with different forms. The researchers have also been studying alternative connection mechanisms that would increase strength and durability, especially for furniture that needs to support the weight of a person over regular use. As they refine these connectors, the same speech driven pipeline could assemble pieces that feel closer to everyday furniture in stiffness and longevity, while still preserving the flexibility that modular design provides.

The robotic arm itself follows toolpaths planned by the system’s control software, which takes into account reach, orientation, and collision avoidance. Each placement must position the block precisely so that neighbouring components align and the object grows according to the voxel blueprint. To demonstrate repeatability, the researchers have assembled the same requested object multiple times, showing that once the system has generated and validated a structure, it can produce that design again without further manual intervention.

Lowering Barriers to Physical Making

One of the central goals of the speech to reality system is to make physical fabrication accessible to people who might never open a CAD program or learn robot programming. The only requirement from the user is a description of what they want, expressed in ordinary language. The language model handles interpretation, the generative AI manages the geometry, and the robot takes care of assembly. For someone who needs a simple stool for a workspace, a compact table for a corner, or a small structure to hold items, the system removes much of the friction that typically comes with designing and building an object.

The underlying research also examines how generative models interact with fabrication constraints. It is one thing to produce a visually appealing 3D model on a screen and another to guarantee that the structure can be built quickly, stand up under load, and be produced with a limited tool set. By coupling the generative step to a discrete assembly method, the team considers factors such as sustainability, material reuse, and overall build time. Modular lattice assemblies can be taken apart and reconfigured, which aligns better with scenarios where space is limited and needs change frequently.

The work has been presented both as a paper and as a live system that builds objects in front of observers. Under the title “Speech to Reality: On-Demand Production using Natural Language, 3D Generative AI, and Discrete Robotic Assembly,” the research describes the full chain of components, from language processing through to physical realization. Results include a range of examples where a six-axis robotic arm completes assembly in minutes, highlighting how the approach can handle multiple object categories without reprogramming the robot for each new design.

Although the current demonstrations focus on small furniture and decorative items, the concepts in the pipeline connect to broader questions about how people interact with tools for making. Instead of thinking in terms of detailed technical specifications, users phrase needs in everyday language and let the system perform the translation into geometry, fabrication steps, and assembly sequences. As the researchers continue to refine both the building blocks and the higher-level models that interpret speech and generate shapes, they are also exploring ways to combine voice control with other interaction modes, including gesture recognition and augmented reality overlays that could show a proposed object in a room before the robot starts building it.